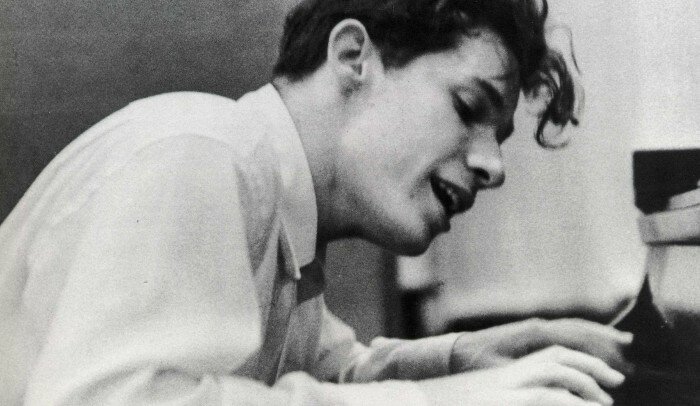

When he stormed the citadels of culture in the mid-‘50s, Glenn Gould was the James Dean of pianists. Rakishly attired and freakishly talented, he packed concert halls from Manhattan to Moscow with the percussive clarity of his play.

But Gould was Canadian, temperamentally unsuited for socializing with wealthy patrons or even sustaining a live-performance career. Gould ceased touring at the height of his popularity, retreated to a radio-recording studio for sonic experimentation and died (as he had predicted) at age 50, in 1982.

There have been several movies about Gould’s music and persona, but befitting its title, Genius Within: The Inner Life of Glenn Gould traces the technique and the ticks to their origins. It benefits immensely from archival materials.

Like Dean, Gould was eminently photographable, and his trademark scarves, unruly hair and low-slung posture at the keyboard were magazine-ready. Fortunately for us, he was also extensively filmed in the studio and at his lakeside retreat, where we see him as a technical perfectionist and an overcoated hermit, respectively.

Gould’s friends and colleagues, including several women with whom he had romantic relationships, contribute recollections, and a music school classmate explains the source of the forceful fingering. Even those of us without a background in classical music can hear why Gould’s recording of Bach’s’ The Goldberg Variations caused such a sensation.

A friend of mine who writes about classical music told me Gould’s music is as divisive today as it was 50 years ago, when the pianist publicly clashed with conductor Leonard Bernstein over the tempo of a performance.

“But,” my friend added, “there’s no question Gould was a genius.”

Sunday, April 10, 2011

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment